We've been so educated and conditioned to think that we deserve what we have (unless we have nearly none, then that is given to us by someone else's hard work and we are just maggots and leeches living off their hard-won bucks), and ironically, the more we have, the more we feel entitled to it. Perhaps greed is to envy what bitterness is to rage.

Consuming. Life-long. Disastrous. Life-defining.

We build entire rationalizations around our passions and entitlements. Especially when what we have belongs to another.

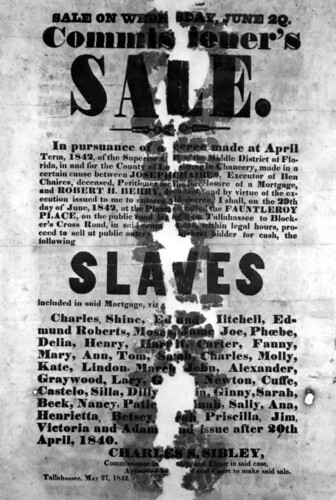

Like the institution of slavery.

Not just rationalizations. But infrastructures and superstructures of rationalizations. Theologians and pastors and scientists were employed to wipe the moral reprehensiveness of generational indentured servitude, brutality, and cultural genocide. And then when that system ended, it began all over again in various forms through Jim Crow laws and various political, spiritual, social, and economic factors that largely kept the Black man indentured to the White power structure in one way or another (I have had people argue that there was really no difference between pre- and post-Civil War for the majority of African Americans in the South. But that shows a lack of understanding of the full degredation of the slave institution at the height of its power). The white power structure, stinging with their greed and bruised egos, decided to redefine the Civil War as a tragic battle of states rights, and that White Supremacist tale continues to live on and grow strength.

And then there's a prominent Republican who bills himself as an anti-racist running around in front of giant Confederate flags and spewing nonsense about how the Civil War wasn't REALLY about slavery,

Ta-Nehisi Coates points out the ridiculousness of these statements. As we've noted before on this blog, anti-Civil War arguments tend to focus on the violence that could have been avoided upon whites, but ignore and/or trivialize the relational, familial, physical, sexual, psychological and spiritual violence that was daily and hourly forced upon black slaves.

[C]omparing figures obscures a larger reality--from the time slavery was introduced to Haiti to the time it left, there was violence. Slavery is violence and any survey of its history violence at its onset, violence at its height, and violence attending its end.

At the heart of this all is the idea that the slave-owners had every right to continue to own slaves until they were done with them. That they owned human beings and had every right to define when and how long and under what circumstances they would give up such rights to their "property."

This is greed in its fullest form. Most of us can now see plainly how evil and warped this form of all-consuming greed was. But it's much harder within the context. When the institutions around us - the literature, the sermons, the television shows, movies, educational system, think tanks,most op-eds, talking heads may say that greed isn't good, but support greed in most of its forms.

We are not allowed to even question our main economic engine for fear of being ostracized. But capitalism runs on greed. It runs on the idea that people are property. We can argue that workers and consumers enter into agreements with capitalist endeavors and are therefore not forced, but that's merely propagandist semantics when there are no viable alternatives for most people. If two thirds of the world have jobs that pay roughly $2 a day, how can we justify this as some sort of "freedom" of economic or social means?

To paraphrase Sartre, There is no exit.

To quote Admiral Akbar, It's a trap!

Yet if we were to look at many of the justifications used to keep the American/Confederate slavery system in place, we can see that Americans of all stripes are using very similar language to justify the global slave market and below-poverty-wage jobs in the US now. You may have used some of these assumptions before. I know I have.

Slavery was vital for the continuance of a superior Southern lifestyle which emphasized good manners and graciousness. Unlike the barbarians.

Slavery was the key to national prosperity—for both the North and the South; nearly 60 percent of U.S. exports of this era were cotton; the slavery advocates argued that if their economy were tampered with, the great industrial cities of the North would crumble; many Southerners viewed the North as a parasite, nourishing itself on slavery while at the same time criticizing it.

The coercion of slavery alone is adequate to form man to habits of labor. Without it, there can be no accumulation of property, no providence for the future, no tastes for comfort or elegancies, which are the characteristics and essentials of civilization.

Mudsill theory is a sociological theory which proposes that there must be, and always has been, a lower class for the upper classes to rest upon. The inference being a mudsill, the lowest threshold that supports the foundation for a building. The theory was first used by South Carolina Senator/Governor James Henry Hammond, a wealthy southern plantation owner, in a Senate speech on 4 March 1858, to justify what he saw as the willingness of the lower classes and the hegemony of non-whites to perform menial work which enabled the higher classes to move civilization forward.

"They [the North] have demanded, and now demand, equality between the white and negro races, under our Constitution; equality in representation, equality in the right of suffrage, equality in the honors and emoluments of office, equality in the social circle, equality in the rights of matrimony. . . . freedom to the slave, but eternal degradation to you and for us"

- William L. Harris, Mississippi's commissioner to Georgia, December 17, 1860

The economy needs it.

Some were born for such work.

They actually enjoy it.

If we allow them the same access we enjoy, we will lose and end up in slavery ourselves.

We do them favors by allowing them to work for us.

They are better off with it then they were without it.

We are teaching them the value of productivity so that they, too, may rise from poverty and into genteelness...

Do these sound familiar?

These are the psychological trappings of the great sin of greed. Forty-one thousand children are dying today from lack of food, and millions - even in the US - have barely enough to survive. Yet our economic system is built on prevailing assumptions that we need what we don't need or even desire. Therefore, what others don't have, what in turn forces them into selling children into prostitution, or crossing geo-political borders without permission, or lives of crime, even, is not our problem and therefore we are, according to our justifications, under no obligation to right those wrongs.

That is, unless we can name our greed for what it is: entitled selfishness and the unrighteous justification that allows us to continually steal from the mouths of starving babes.

The counter to this, of course, is charity. Not charity of individuals. But charity of society.

Not the charity as we currently frame the phrase - a few dimes thrown in support of a cause celebrè. But rather an over-reaching, fundamental power of investment and justice for those deprived of basic human needs and rights.

More on that later...

No comments:

Post a Comment

Be kind. Rewind.